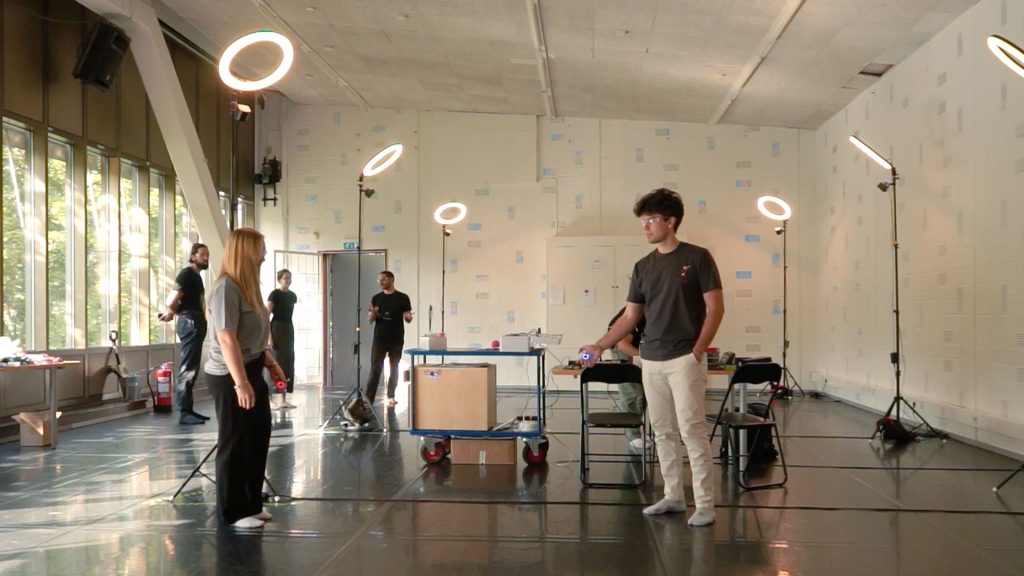

Bitcraze will exhibit at the European Robotics Forum 2026 March 23-27 in booth #90, where we will demonstrate a live, autonomous indoor flight setup based on the CrazyflieTM platform. The demonstration features multiple nano-drones flying autonomously in a controlled environment and reflects how the platform is used in research and applied robotics development.

Why Indoor Aaerial Testbeds Matter

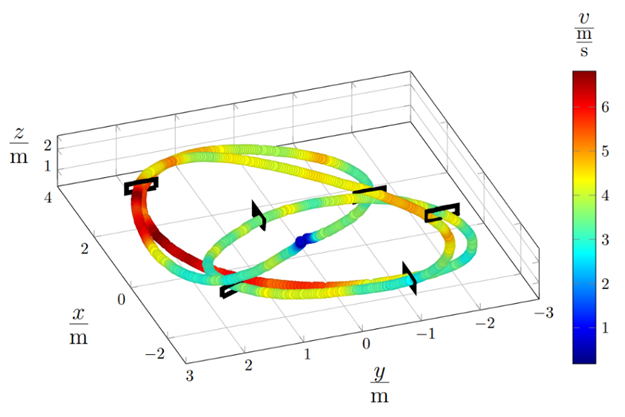

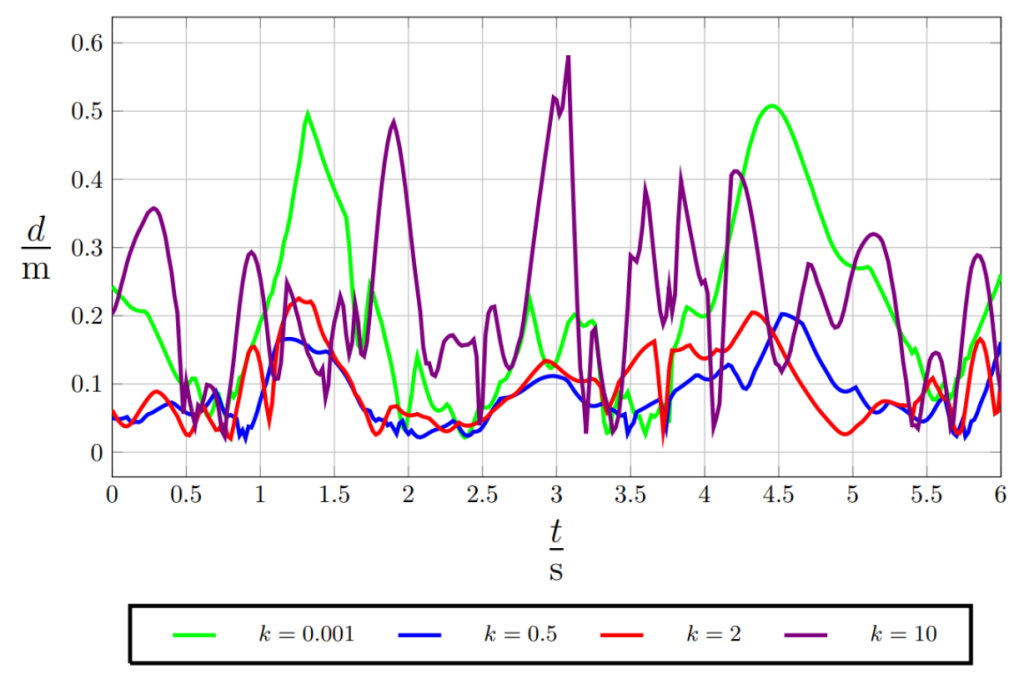

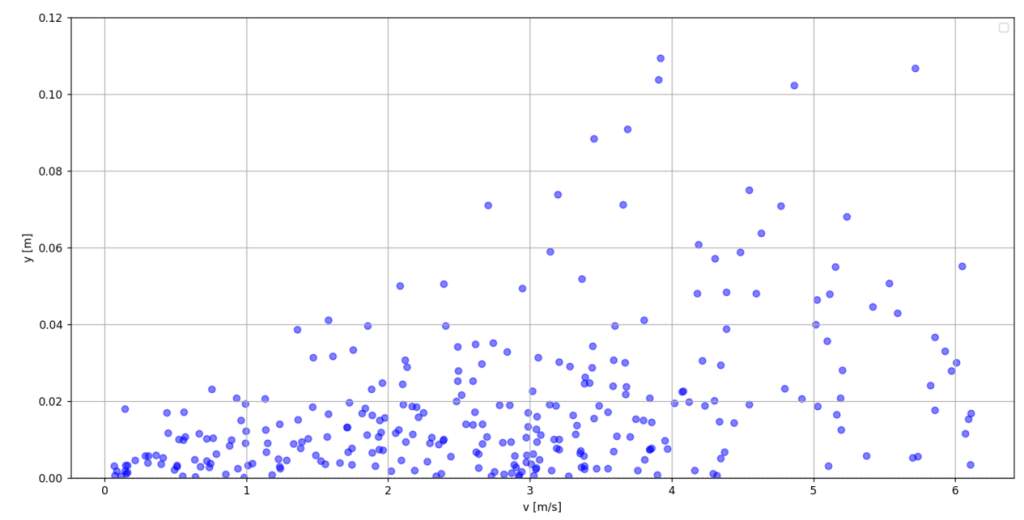

The purpose of the demonstration is not the flight itself, but the role such setups play in validating aerial robotics concepts. Indoor, small-scale aerial systems allow researchers and R&D teams to study autonomy, perception, control, and multi-robot coordination under safe and repeatable conditions. This makes it possible to explore system behavior, test assumptions, and iterate rapidly before moving to larger platforms or less controlled environments.

Applicable in Both Academia and Industrial R&D

Bitcraze is used both in academic research and in industrial R&D contexts. In academia, the platform supports experimental work in areas such as swarm robotics, learning-based control, and human–robot interaction, and has been referenced in hundreds of peer-reviewed research papers worldwide. In industry, similar setups are increasingly used as testbeds to de-risk development by validating ideas indoors before scaling to outdoor testing, larger drones, or other robotic systems that require higher investment and operational complexity.

Hands-on Discussions at the Booth

At the booth, the live flight cage will be complemented by hands-on access to additional drones, expansion decks, and software tools. This allows for technical discussions around hardware architecture, sensing and positioning options, software stacks, and how different configurations support different research or development goals.

The Conversations We Are at ERF to Have

At ERF, Bitcraze is there to engage in conversations about platforms, testbeds, and how ambitious aerial robotics ideas can be validated in a financially responsible, safe, and controlled manner. This includes discussions with academic groups, industrial R&D teams, and project partners working across the research-to-application spectrum.

Looking forward to the discussions in Stavanger in booth #90!

Send us a message to contact@bitcraze.io to book a meeting at the show!