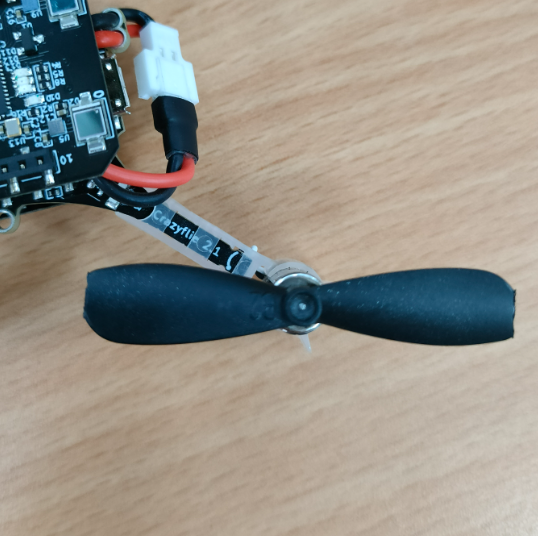

We are excited to announce that we are working on several new link performance metrics for the Crazyflie that will simplify the troubleshooting of communication issues. Until now, users have had access to very limited information about communication links, relying primarily on a “link quality” statistic based on packet retries (when we have to re-send data) and an RSSI channel scan. Our nightly tests have been limited to basic bandwidth and latency testing. With this update, we aim to expose richer data that not only enables users to make more informed decisions regarding communication links but also enhances the effectiveness of our nightly testing process. In this blog post, we will explore the new metrics, the rationale behind their introduction, and how they will improve your interaction with the Crazyflie. Additionally, we will be holding a developer meeting on Wednesday November 13th to discuss these updates in more detail, and we encourage you to join us!

“Link Quality”—All or Nothing

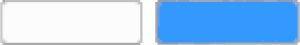

Until now, users of the Crazyflie have had access to a single link quality metric. Implemented in the Python library, this metric is based on packet retries—instances when data packets need to be re-sent due to communication issues. This metric indicates that for every retry, the link quality drops by 10%, with a maximum of 3 retries allowed. As a result, the link quality score usually ranges from 70% to 100%, with a drop to 0% when communication is completely lost. However, as packet loss occurs, users often experience a steep decline, commonly seeing 100% when packets are successfully acknowledged or dropping to 0% when communication is completely lost.

The current link quality metric has served as a basic indicator but provides limited insight, often making it difficult to gauge communication reliability accurately. Recognizing these limitations, we’re introducing several new link performance metrics to the Crazyflie Python library, designed to provide a far more detailed and actionable view of communication performance.

What’s Coming in the Upcoming Update

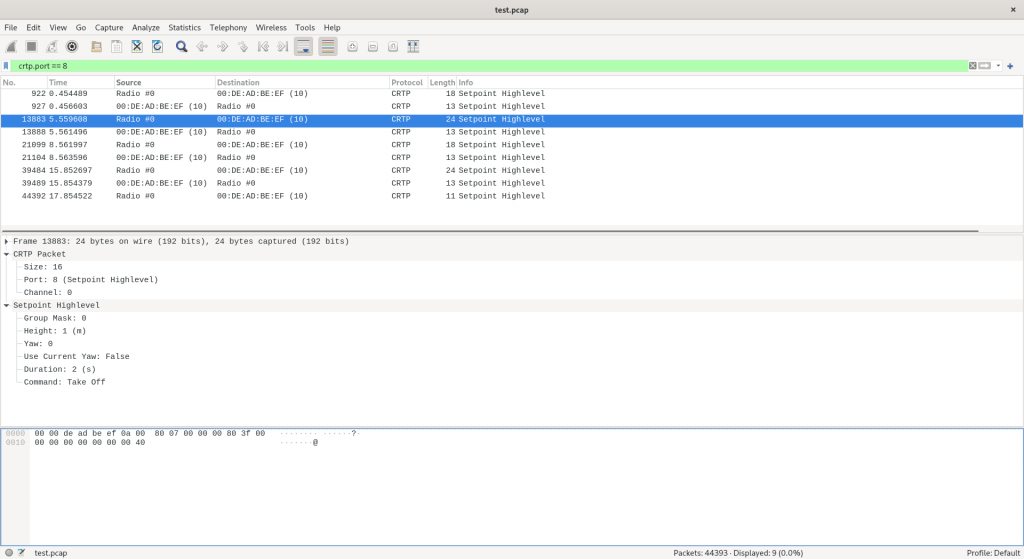

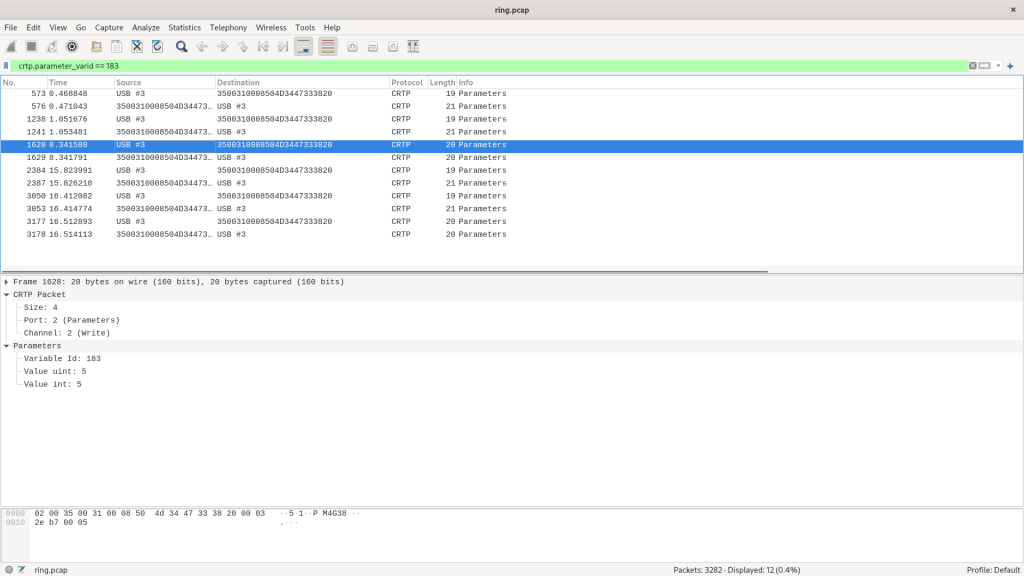

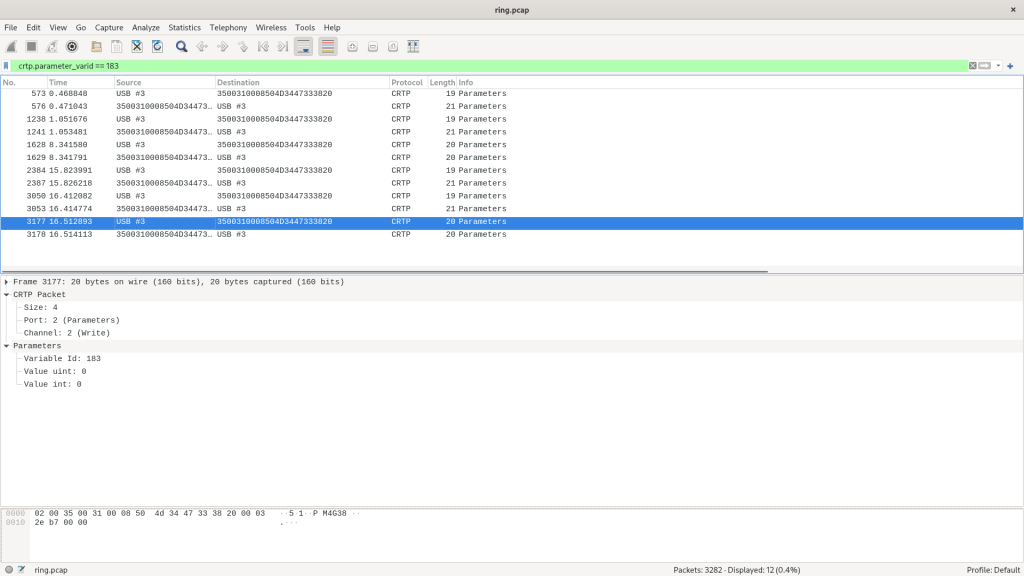

The first metric we are adding is latency. We measure the full link latency, capturing the round-trip time through the library, to the Crazyflie, and back. This latency measurement is link-independent, meaning it applies to both radio and USB connections. The latency metric exposed to users will reflect the 95th percentile—a commonly used measure for capturing typical latency under normal conditions.

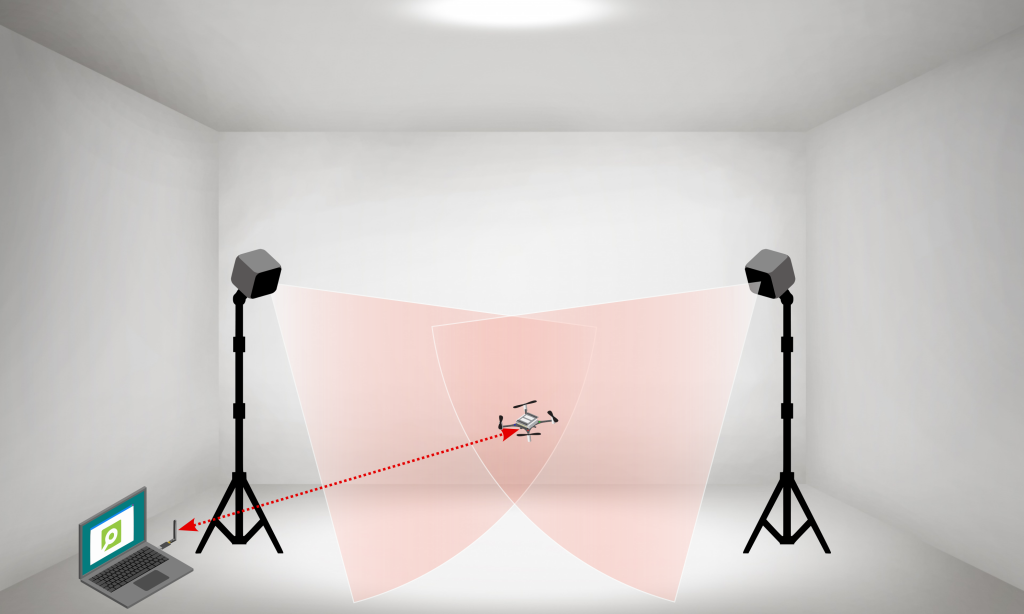

Next are several metrics that (currently) only support the radio link. For these, we distinguish between uplink (from the radio to the Crazyflie) and downlink (from the Crazyflie to the radio).

The first is packet rate, which simply measures the number of packets sent and received per second.

More interestingly, we are introducing a link congestion metric. Whenever there is no data to send, both the radio and the Crazyflie send “null” packets. By calculating the ratio of null packets to the total packets sent or received, we can estimate congestion. This is particularly useful for users who rely heavily on logging parameters or, for example, stream mocap positioning data to the Crazyflie.

The Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI) measures the quality of signal reception. Unlike our current “link quality” metric, we hope that a poor RSSI will serve as an early warning signal for potential communication loss. While RSSI tracking has been possible before with the channel scan example, this update will monitor RSSI in the library by default, and expose it to the user. The nRF firmware will also be updated to report RSSI by default. Currently, we only receive uplink RSSI, that is, RSSI measured on the Crazyflie side.

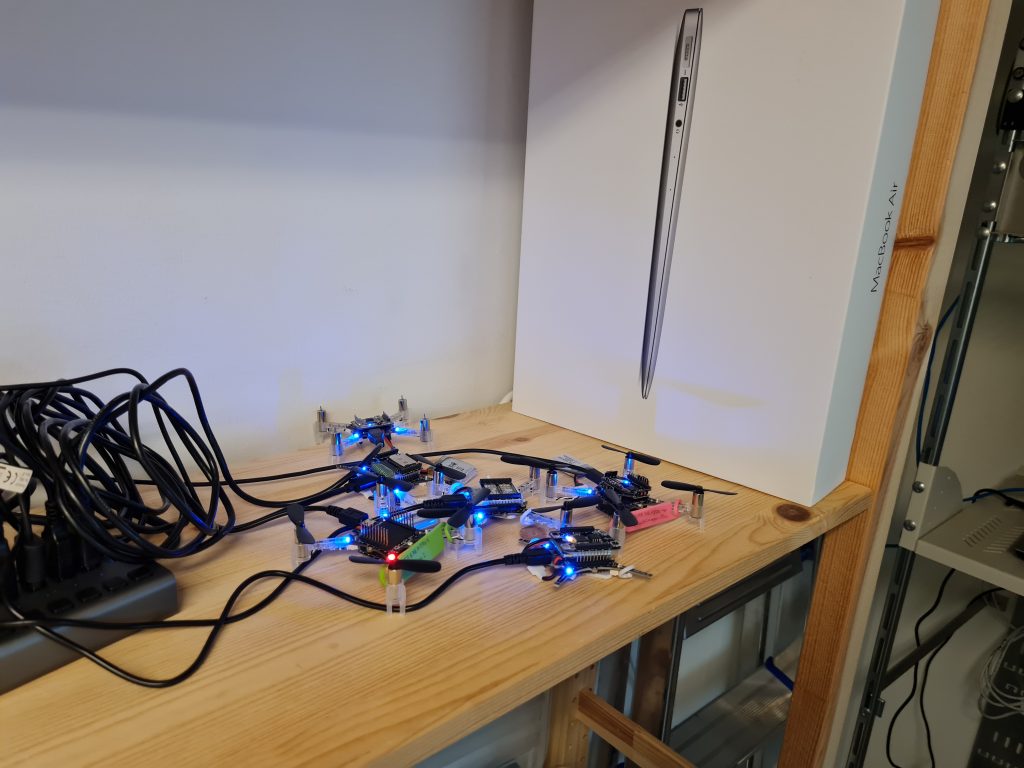

We’ve already found these new metrics invaluable at Bitcraze. While we have, of course, measured various parameters throughout development, it was easy to lose track of the precise status of the communication stack. In the past, we relied more on general impressions of performance, but with these new metrics, we’ve gained a clearer picture. They’ve already shed light on areas like swarm latency, helping us fine-tune and understand performance far better than before.

You can follow progress on GitHub, and we invite you to try out these metrics for yourself. If there’s anything you feel is missing, or if you have feedback on what would make these tools even more helpful, we’d love to hear from you. Hit us up over on GitHub or join the developer meeting on Wednesday the 13th of November (see the join information on discussions).