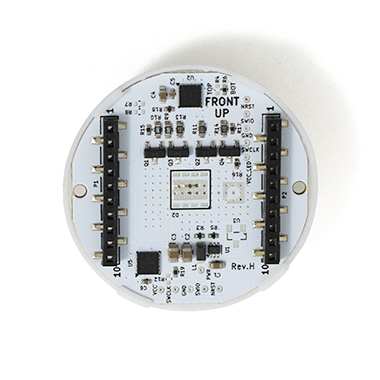

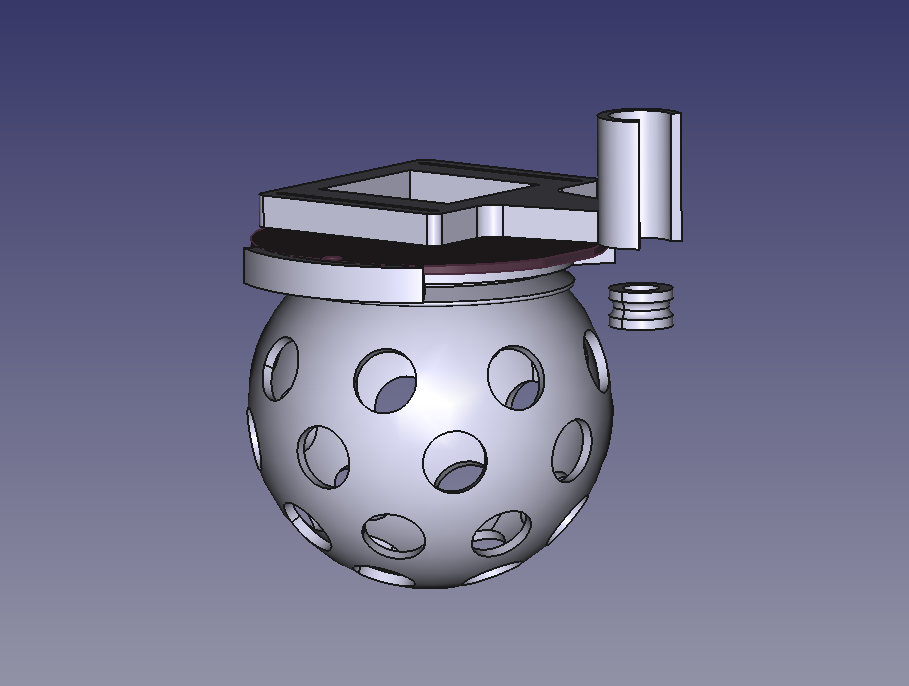

The CrazyflieTM Color LED deck is a high-powered, fully programmable RGB(W) lighting expansion for the Crazyflie 2.x platform —and it’s now available in the shop.

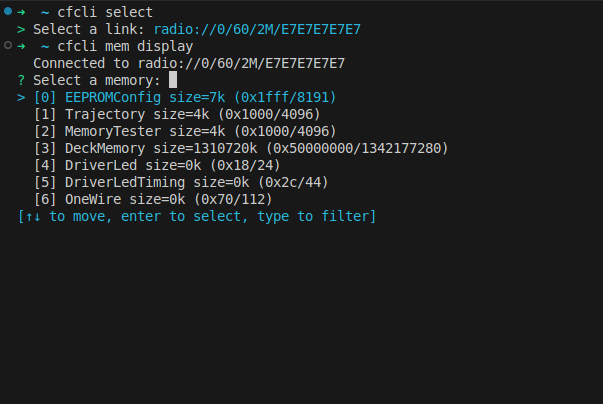

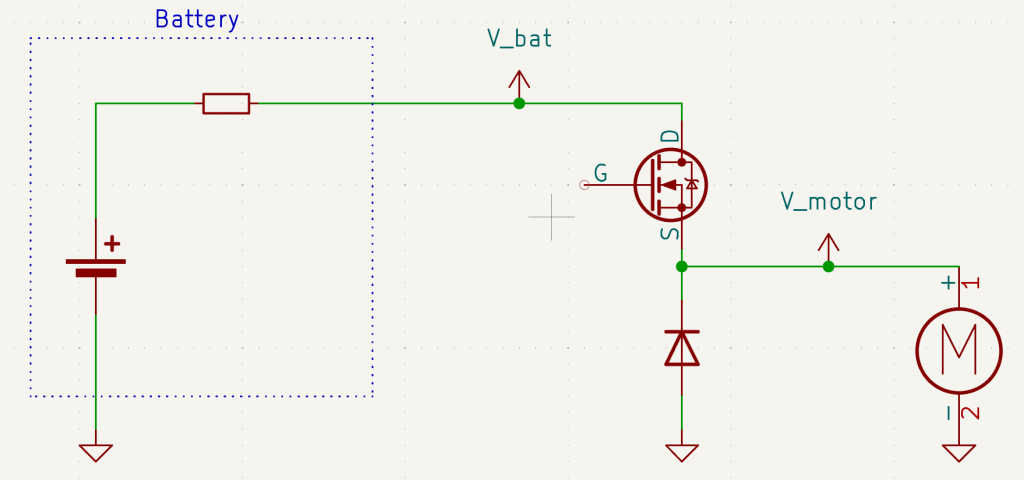

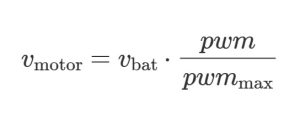

It delivers bright, diffused, and uniform light suitable for research, teaching, vision experiments, and indoor drone choreography. The deck mounts on top or bottom of the Crazyflie and integrates seamlessly through our open-source firmware and I²C-based deck interface.

Two Versions, Same Electronics

The Color LED deck is available in two distinct versions, each sold as a separate product.

Top-Mounted Color LED Deck

Designed to be placed on top of the Crazyflie. Ideal for scenarios where the drone is viewed from above or when customers need to use positioning or sensor decks underneath the Crazyflie—such as the Flow Deck or other bottom-mounted modules.

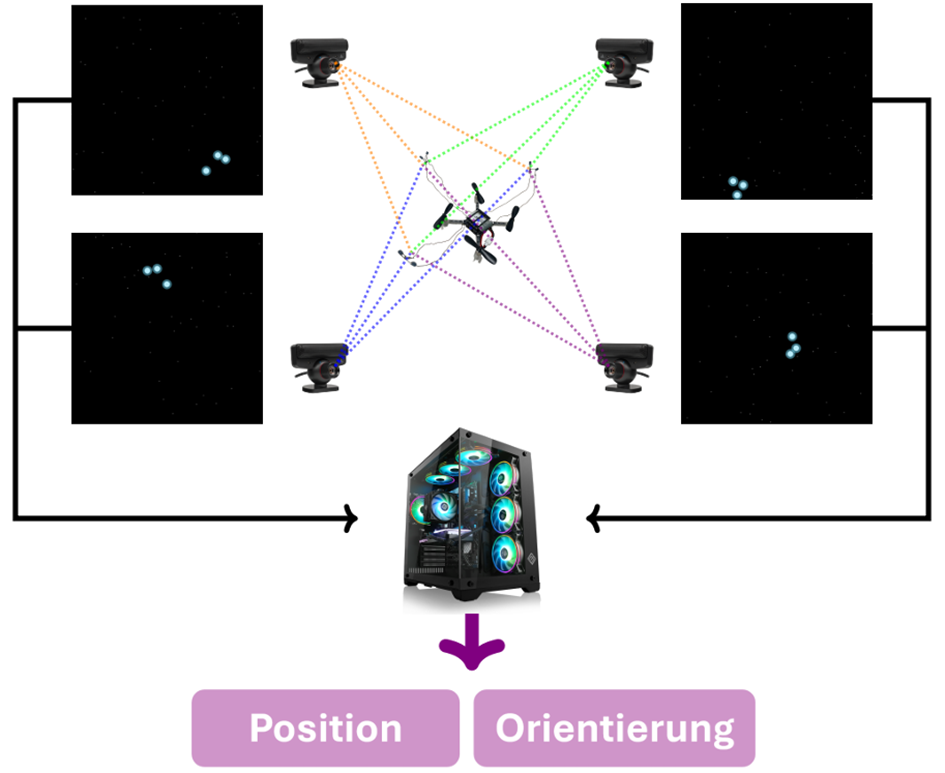

- Works well with motion capture (MoCap) systems using ceiling-mounted cameras.

- Not recommended with the Lighthouse positioning deck, due to optical occlusion and interference with the lighthouse sensors.

You can find the top-mounted version in the store here

Bottom-Mounted Color LED Deck

This version is suitable for almost all use cases, offering maximum visibility from below and minimal interference with other decks.

- Ideal for Lighthouse positioning (no optical obstruction).

- Ideal for MoCap positioning, especially when cameras view from multiple angles

You can find the bottom-mounted version in the store here.

Dual Mounting for Maximum Visibility

Additionally, two Color LED decks can be mounted both above and underneath the Crazyflie simultaneously, creating a strong, uniform light signature visible from all directions. This is best for MoCap environments where multi-angle visibility improves marker/camera performance.

You can see all three variants of the Color LED in action in our latest Christmas video, created in collaboration with Learning Systems and Robotics Lab :

Each color LED deck variant operates independently, allowing the top and bottom decks to be configured with different colors if desired. While all variants share the same electronics, diffuser, and firmware behavior, their physical mounting positions let you choose the setup that best fits your lab, show environment, or positioning needs.

Diffuser now available

While designing the Color LED deck, we also created a light diffuser—now available in the shop to buy as a standalone product. It is designed to be compatible with the LED ring to spread and soften the light, extending visibility and improving appearance.

You can find the light diffuser in the store here.

The Color LED deck is available now in both versions. Head to the store to order, or contact us for a quote!