Hey, Victor here!

As some of you may know, I’ve worked at Bitcraze for two summers (2019, 2020), and I did my Bachelor’s thesis here during the spring this year. While we mentioned shortly that I started working on my thesis (here), I never presented the results of it, so I thought that I’d do that now! Better late than never, right?

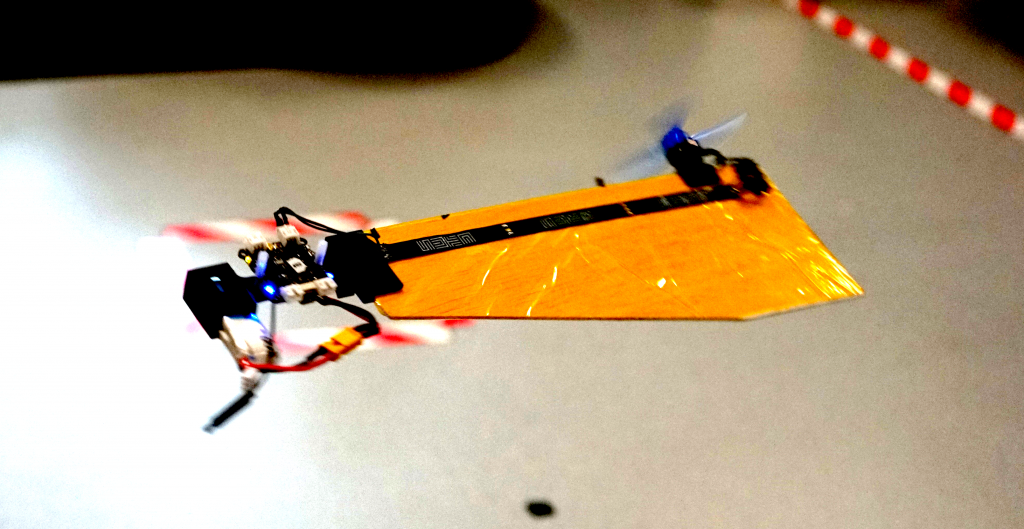

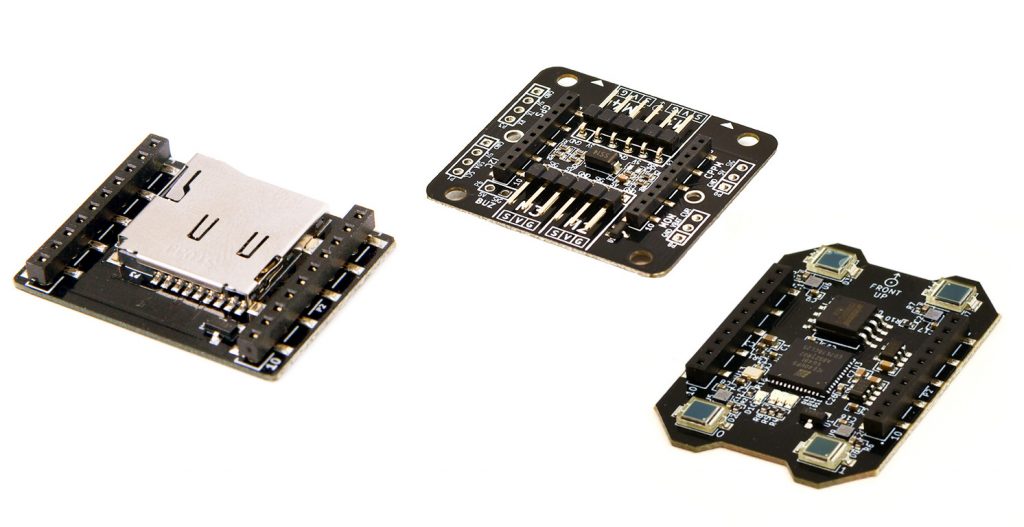

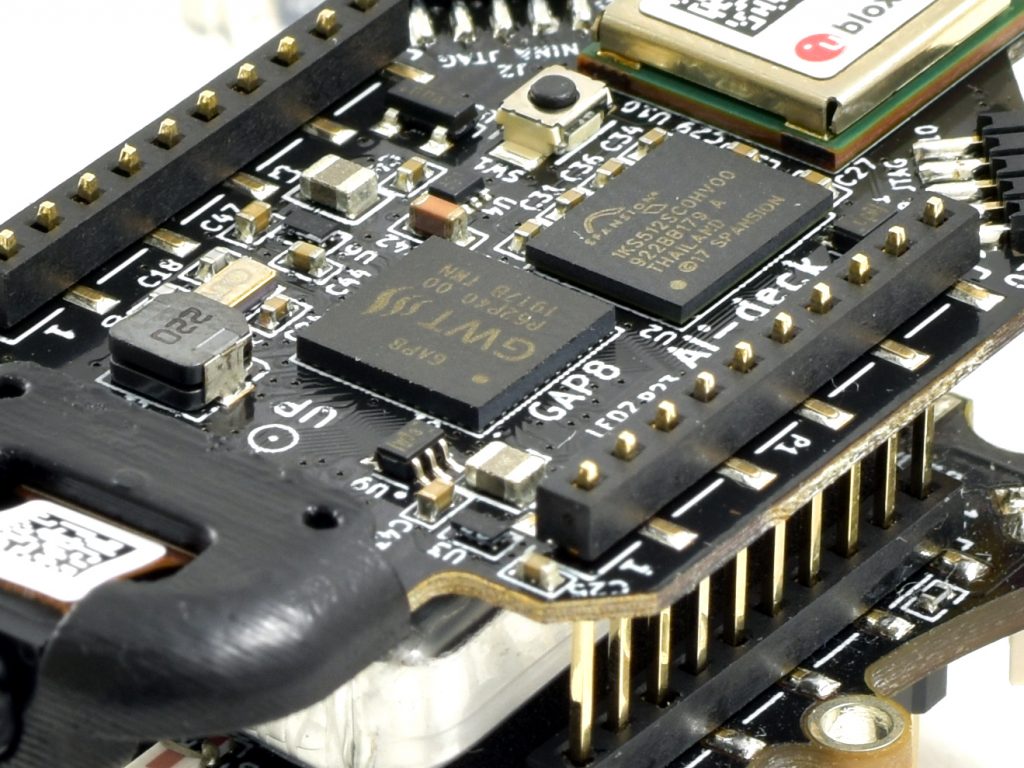

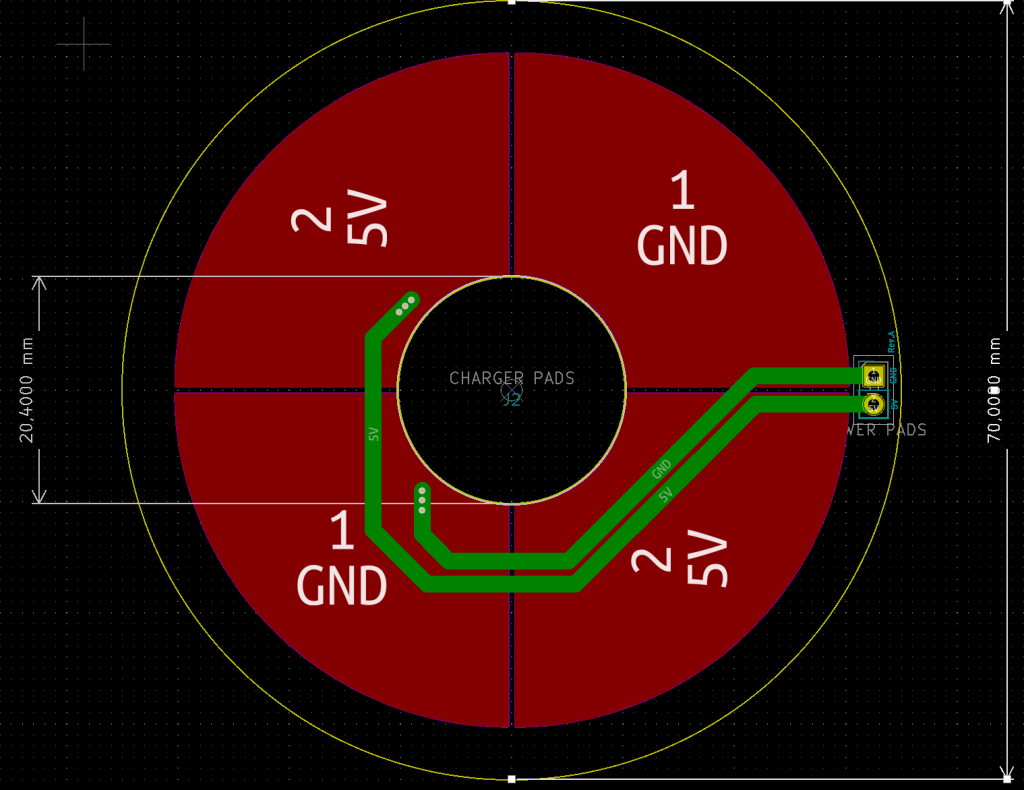

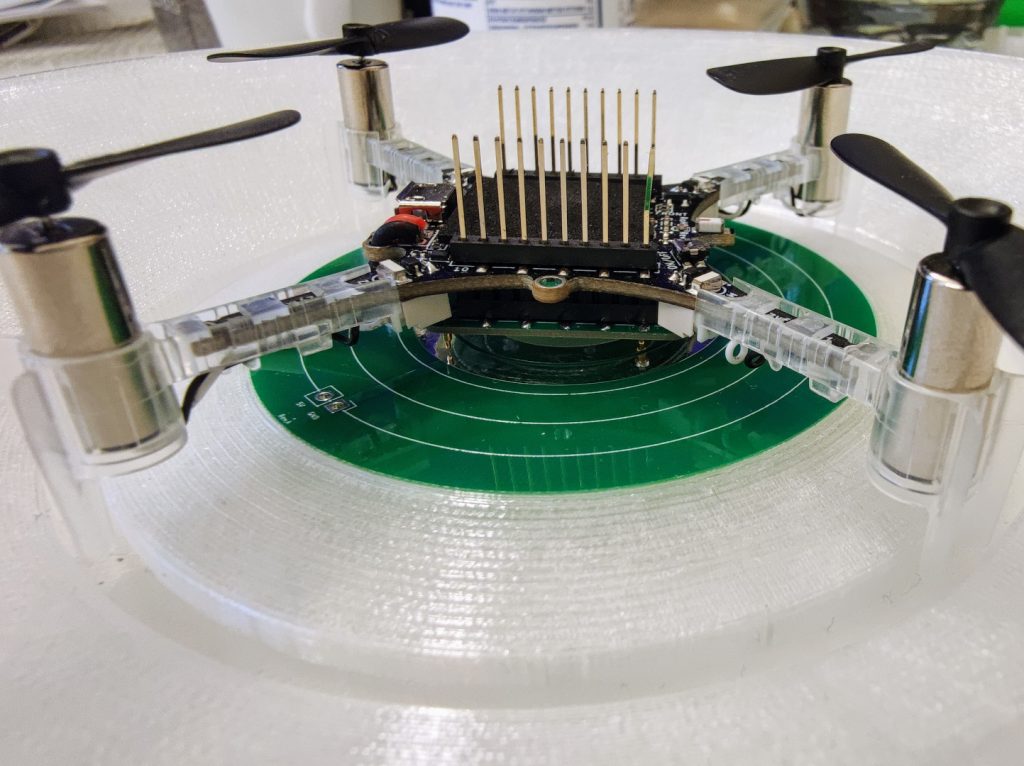

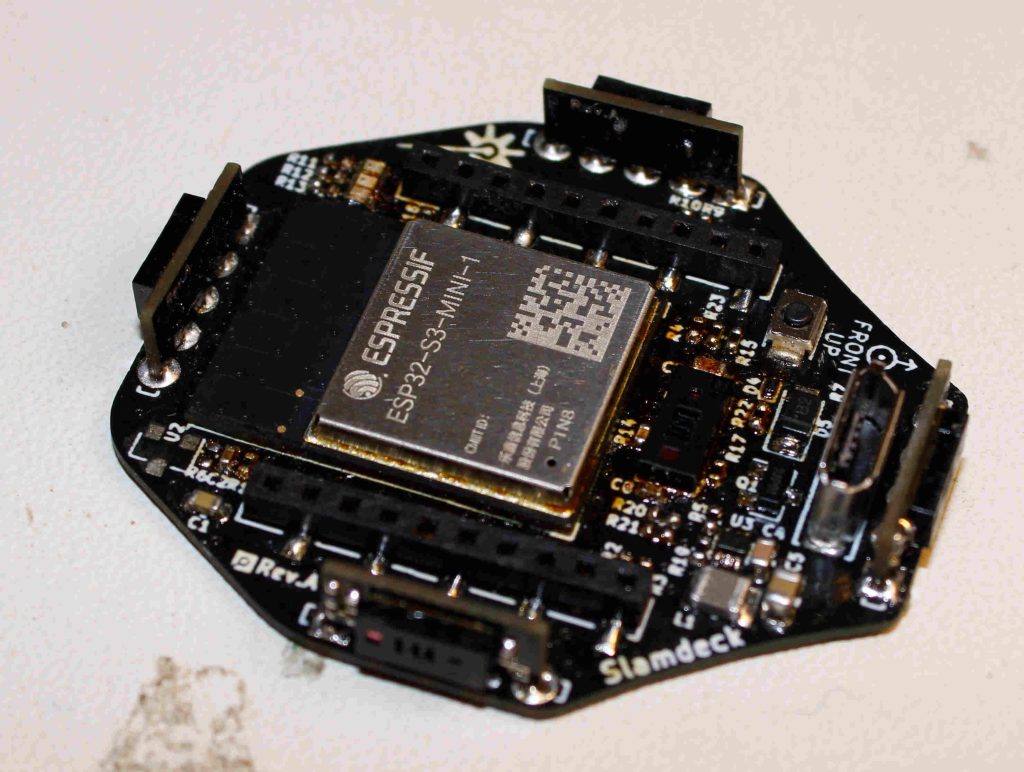

So, during my thesis I built a prototype deck for the Crazyflie which contained five multizone lidar sensors (VL53L5CX) and an ESP32-S3. The VL53L5CX sensors can output distances to a 8×8 grid, with a 45 degrees FoV at a rate of 15 hz. The purpose of the ESP32-S3 was to collect the data from the sensors and send it to a ground control station, either with WiFi, or, with the nRF radio on the Crazyflie. While the ESP32-S3 is quite overkill for only collecting data and send it, we weren’t sure of how much data that would be gathered from the sensors, so to be on the safe side we rolled with the ESP32-S3. Both the sensors and the microcontroller was very new at the time so it seemed like a good oportunity to try them out.

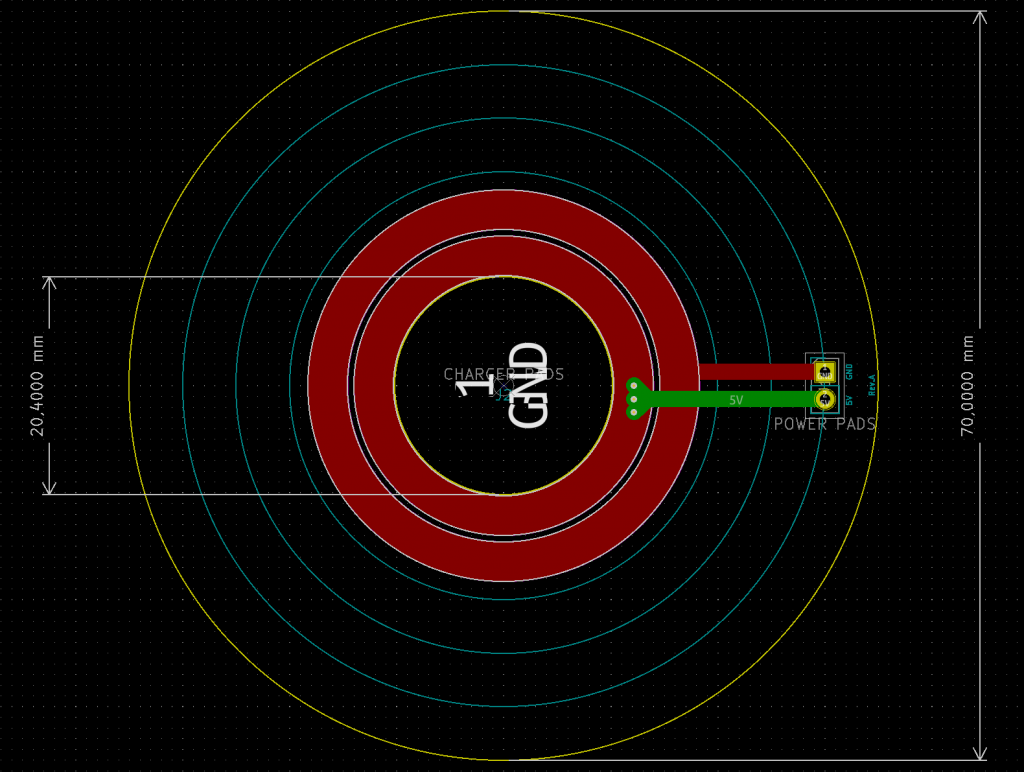

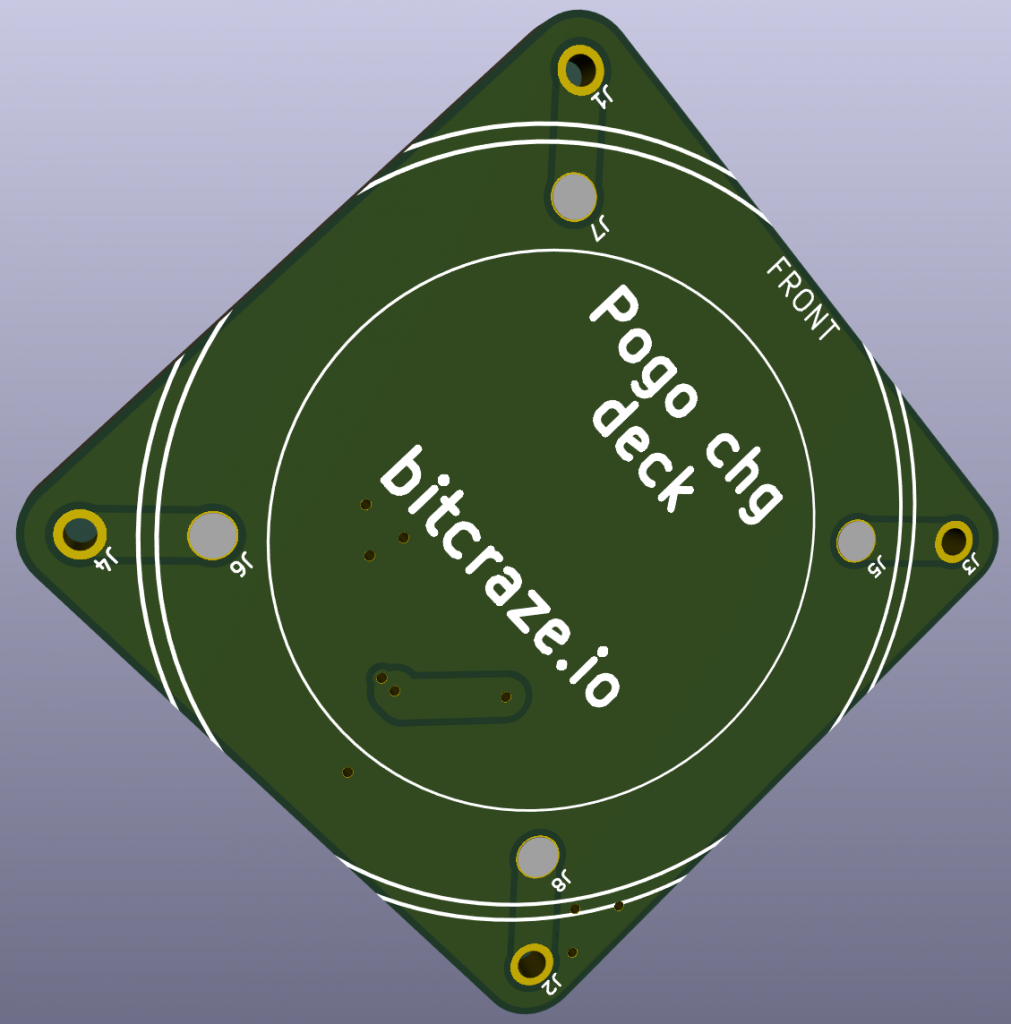

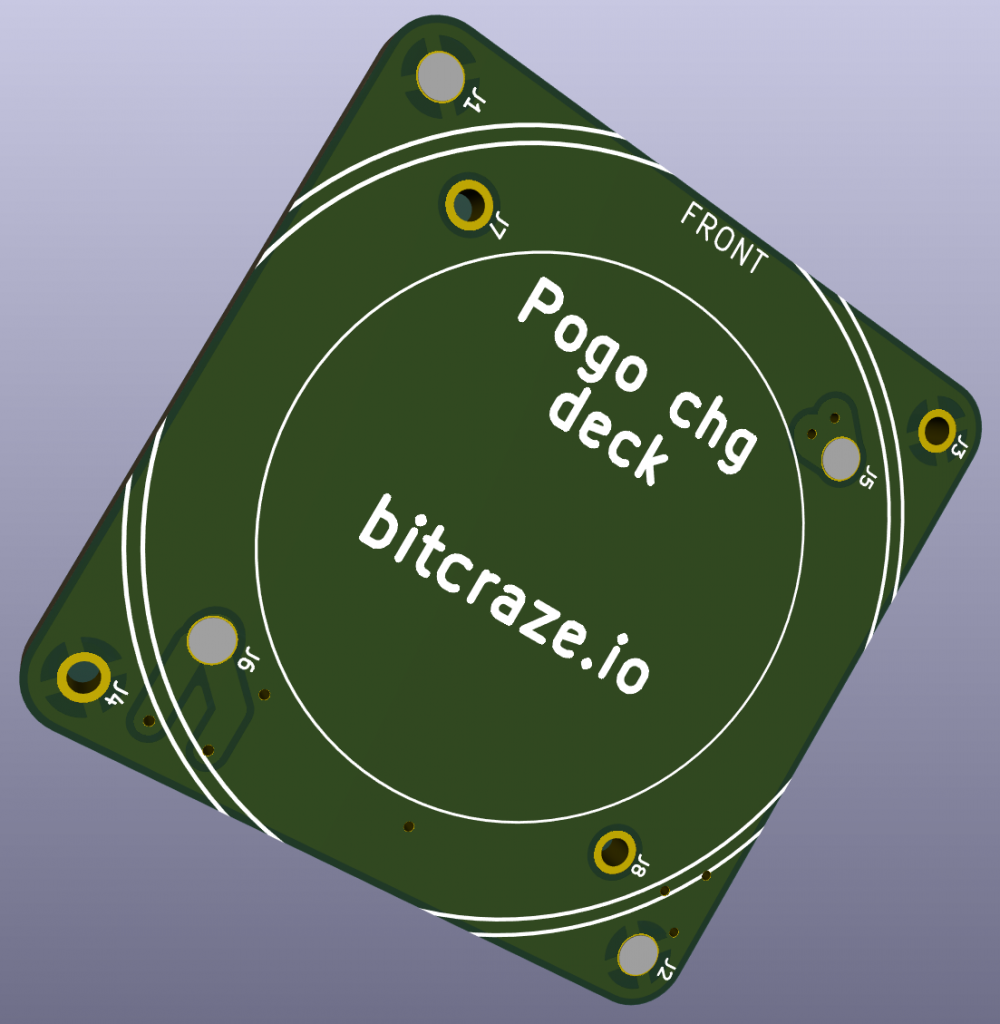

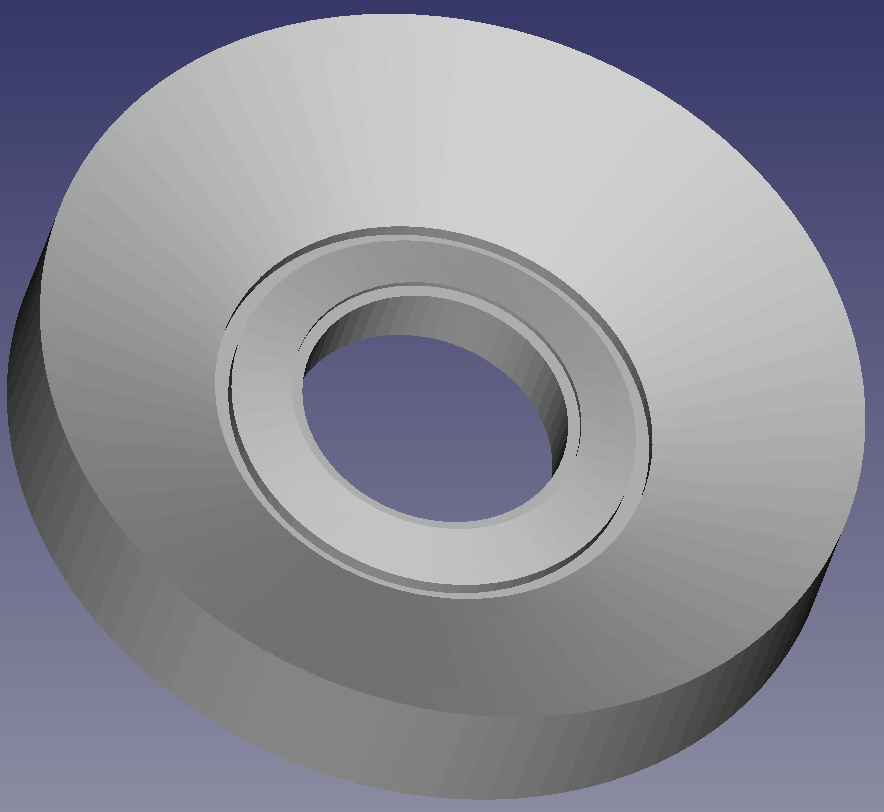

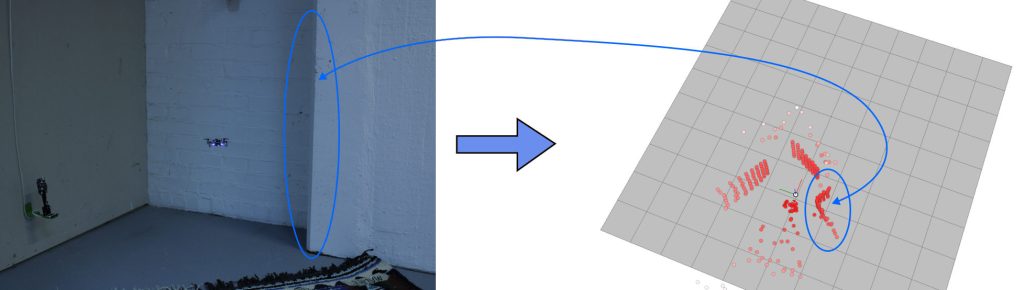

I designed the schematic in KiCad and got a lot of help from everyone here at Bitcraze while doing so, especially Tobias. Once the schematic was done I designed the PCB, ordered the components and then waited eagerly for the stuff to arrive. Once everything had arrived, I soldered all components and assembled the deck. I then wrote some firmware for the ESP32-S3, and the STM32 on the Crazyflie, and at last I wrote a simple GUI in PyQt to help visualize the data, both in 2D and 3D.

The deck was quite successful and while the GUI was very far from perfect, I think it did show that the deck has some nice potential and it was very cool to see the 3D point cloud in realtime while flying the Crazyflie! I tried sending the data over WiFi which worked perfectly well, and I also tried sending it through the nRF on the Crazyflie with the help of CPX, which also worked pretty well.

If you’re more curious about the thesis, feel free to check it out here, and the github repository can be found here.

I finished the thesis in the beginning of the summer, and I have been working part time here at Bitcraze since September and I’ve truly been loving! I think it’s been really cool to become a part of the team and work more on the regular stuff that the rest of the team does. It has been very interesting to see how the team works and cooperates on a daily basis. Something that striked me was just how many products and different features and services we handle here, with only six people!

Fortunately and unfortunately, I will be moving to Gothenburg next week which means that my time at Bitcraze is over, for this time. I have learned a lot from everyone here and truly appreciate all the love and support, which actually started before I even started my Bachelor’s degree.

Cheers and (early) Merry Christmas,

Victor